|

Pertussis, better known as whooping cough, is an infectious disease caused by the bacterium – Bordetella pertussis. It can cause serious illness, which can be especially severe in young babies. There are two types of pertussis vaccine used in global vaccination programmes – the whole cell pertussis vaccine (wP) and the acellular pertussis vaccine (aP). Neither vaccine contains live bacteria, and the vaccines cannot cause the disease itself. Both vaccines protect against pertussis infection. The wP vaccine contains the killed whole cells of the pertussis bacteria. The whole cell pertussis vaccine (wP) was used in the UK infant vaccination programme until 2004 when it was replaced by the acellular pertussis vaccine (aP). The acellular pertussis vaccine replaced the wP vaccine in the UK as it causes less fever, and local reactions (such as swelling and pain in the leg where the vaccine was given). The acellular pertussis vaccine (aP) contains between three and five proteins purified from the pertussis bacteria. The vaccine is not available on its own. It is given in combination vaccines to babies and young children in the UK as part of the 6-in-1 vaccine, and the 4-in-1 pre-school booster. Pregnant individuals are also offered the pertussis pre-school booster vaccine from week 16 of their pregnancy, to protect their infant once they are born but too young to be vaccinated. For more information about please read the section below - pertussis vaccination in pregnancy.

|

Pertussis/whooping cough vaccine

Vaccine

|

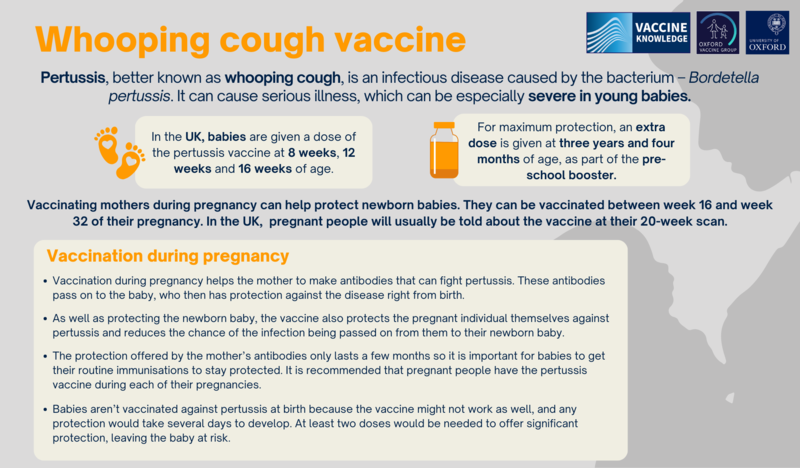

In the UK babies are given a dose of the pertussis vaccine at 8 weeks, 12 weeks and 16 weeks of age – a total of three doses, as part of the 6-in1 vaccine. For maximum protection, this is further boosted when they reach three years and four months of age, as part of the pre-school booster. Those who are pregnant are also offered the pertussis vaccine. In the UK, this usually coincides with their 20-week scan, although it can be given from week 16 of pregnancy, up until week 32. This is because of the risk whooping cough poses to newborn babies, who are not vaccinated until they are eight weeks old in the UK, and are not fully protected until after their third dose of vaccine at four months of age. |

|

All the pertussis-containing vaccines used in the UK have been rigorously tested and shown to be safe. Like all medicines, vaccines can cause side-effects but not everybody experiences them. For more information about how vaccines are made and tested, please watch this film. 6-in-1 pertussis containing vaccineAfter each dose of the 6-in-1 vaccination, a baby may experience some side-effects. Depending on how many infants experience these side-effects, they are classed as very common, common, rare, or very rare. Very common - more than 1 in 10 may experience these following each dose:

Many of these symptoms can be relieved by giving paracetamol (Calpol) if your child is over two months old, or ibuprofen (Nurofen) if your child is over three months and weighs more than 5kg. For advice on giving painkillers to babies and children, please see NHS Choices. Common – these may affect up to 1 in 10 infants at each dose:

Rare - these may affect up to 1 in 1000 infants at each dose:

Very rare - affecting fewer than 1 in 10,000 infants at each dose:

Hypotonic-hyporesponsive episodes (HHE) are a rare side-effect associated with the whole cell pertussis (wP) vaccination. Typically an infant may become blue, pale and/or limp for a short period in the hours following immunisation and then recover quickly back to normal with no long-term effects. The infants can be safely given subsequent doses of the same vaccine as the episodes do not usually occur with subsequent doses. These episodes, although rare, were more common following vaccination with the whole cell pertussis vaccine used up to 2004. Since the introduction of the acellular pertussis (aP) vaccines, HHE are very, very rare. You should consult your doctor if your child experiences fits or HHE episodes after vaccination. This is mainly to check that it is the vaccine causing the symptoms, and not some unrelated disease. Symptoms such as fits can be very worrying for parents, but there is no evidence of long-term effects. Children can normally safely receive vaccines in the future. For more information on febrile seizures generally, see NHS Choices. Pre-school pertussis containing booster (Boostrix-IPV)Side effects that occurred during clinical trials in children from the age of four to eight years: Very common - these may occur with more than 1 in 10 doses of the vaccine:

Common - these may occur with up to 1 in 10 doses of the vaccine:

Uncommon - these may occur with up to 1 in 100 doses of the vaccine:

Many of these symptoms can be relieved by giving paracetamol (Calpol) if your child is over two months, or ibuprofen if your child is over three months and weighs more than 5kg. See the NHS Website for more advice on giving painkillers to babies and children. Pertussis-containing Boostrix-IPV in adultsVery common - affecting more than 1 in 10 people at each dose:

Common - affecting up to 1 in 10 people at each dose:

Uncommon - affecting up to 1 in 100 people at each dose:

For rarer side effects (affecting fewer than 1 in 1000 people), see the patient information leaflet for Boostrix-IPV . As with any vaccine, medicine or food, there is a very small chance of a severe allergic reaction (anaphylaxis). Anaphylaxis is different from less severe allergic reactions because it causes life-threatening breathing and/or circulation problems. It is always extremely serious but can be treated with adrenaline. Healthcare workers who give vaccines know how to do this. In the UK between 1997 and 2003 there were a total of 130 reports of anaphylaxis to the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) following ALL immunisations. Put into context, around 117 million doses of vaccines were given in the UK during this period. This means that the overall rate of anaphylaxis is around 1 in 900,000. If you are concerned about any reactions that occur after vaccination, consult your doctor. In the UK you can report suspected vaccine side effects to the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) through the Yellow Card Scheme . You can also contact the MHRA to ask for data on Yellow Card reports for individual vaccines . See more information on the Yellow Card scheme and monitoring of vaccine safety. |

|

The acellular pertussis vaccines (aP) all contain proteins from the pertussis bacteria, rather than the whole cell. Apart from the active ingredients (the antigens), which produce the immune response, these pertussis-containing vaccines also include very small amounts of other ingredients. None of them contain porcine gelatine. Boostrix-IPV (used in the UK for the pre-school booster and in pregnancy)In addition to the active ingredients that produce the immune response to diphtheria, pertussis/whooping cough, polio and tetanus, and water, Boosterix-IPV contains:

The polio part of the vaccine is grown in the laboratory using cultured animal cells. Other brands of pertussis-containing vaccine offered to pregnant women in other countries may contain different ingredients. If you are not in the UK, ask for the patient information leaflet for the vaccine you are offered. Infanrix hexa and Vaxelis (used in the UK for the 6-in-1)Apart from the active ingredients (antigens) that produce the immune response to diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis/whooping cough, polio, Hib and hepatitis B, these vaccines contain water and very small amounts of other added ingredients. Many of these are already found naturally in the body or food. Added ingredients include, but are not limited to:

The final vaccine may also contain traces of these products that are used during the manufacturing process:

Some of the active ingredients for these vaccines are grown in a laboratory. This includes:

Other brands of the 6-in-1 vaccine used in non-UK countries may contain different ingredients. If you want to find out more about the specific ingredients of the vaccine you are offered, ask for the specific patient information leaflet. You can also read more about vaccine ingredients here. |

|

Babies under the age of three months are at greatest risk complications and death from pertussis, yet they are not fully protected until they have had the three doses of vaccine between the age of 8 weeks and 16 weeks. Vaccinating mothers during pregnancy can help protect these newborn babies. Pregnant people can be vaccinated any time after week 16 of their pregnancy up until 32 weeks. In the UK, those who are pregnant will usually be told about the vaccine at their 20 week scan. How does vaccinating during pregnancy help protect new born babies?Vaccination during weeks 16 to 32 of pregnancy helps the mother to make antibodies that can fight pertussis. It takes about two weeks for antibody levels to peak. These antibodies are then transferred through the placenta to the baby, who then has the mother’s own protection against the disease in their blood right from birth. Very small quantities of pertussis antibodies may also be transferred to the baby through breast milk. As well as protecting their newborn baby, the vaccine also protects the pregnant individual themselves against pertussis, and therefore reduces the chance of the infection being passed from them to their newborn baby. Although those who are pregnant can be vaccinated any time up until labour, it is advised they are vaccinated before week 32 because it takes about two weeks for the immune system to make antibodies and pass these across to the unborn baby. The protection offered by the mother’s antibodies lasts only a few months. It is therefore important for babies to get their routine immunisations (see the 6-in-1 vaccine) when they are two, three and four months old, so they continue to be protected. It is recommended that people have the pertussis vaccine in each of their pregnancies, even if they have been previously vaccinated. Why not vaccinate babies against pertussis at birth?There are two reasons why vaccinating babies at birth does not offer them the best protection against pertussis. First, newborn babies’ immune systems may have a lower response to a dose of pertussis vaccine given early in life. Second, vaccination does not offer immediate protection. It takes several days for a baby’s immune system to respond to the vaccine, and at least two doses of vaccine are needed to give significant levels of protection. What vaccine is given during pregnancy?The pertussis vaccine is only available in combination with other vaccines. The vaccine offered during pregnancy in the UK is called Boostrix-IPV, which is also used as a pre-school booster vaccine. This vaccine also protects against diphtheria, tetanus and polio. The vaccine does not contain any live bacteria or viruses, and cannot cause any of the diseases it protects against. As with the pre-school booster, one dose is given during pregnancy. It’s worth noting that Boostrix-IPV can be given safely at the same time as the flu vaccine, if the recommended timings coincide. For more information, please read the Boostrix-IPV patient information leaflet. An alternative to Boostrix-IPV, which will not contain the polio vaccine component, is going to be introduced in the UK from mid-2024 onwards. The vaccine, Adacel, (TdaP) protects against tetanus and diphtheria, as well as whooping cough. For more information about Adacel, please read the patient information leaflet. Is the pertussis vaccine safe in pregnancy?If you are pregnant, it is understandable to be worried about any potential effects of a vaccine on an unborn child. There is good evidence that the recommended pertussis vaccine can be given safely in pregnancy without causing harm to mother or to baby. All vaccines recommended for pregnant people have been thoroughly assessed in large clinical studies of pregnant women to ensure they are safe. And there is considerable experience of its use both in the UK and the United States. Boostrix-IPV has also been used extensively in Australia, New Zealand and other countries. These combination vaccines are being used because a single pertussis vaccine is not available. Boostrix-IPV contains low-dose diphtheria and tetanus, which means that the rate of side effects is lower than with the 6-in-1 vaccine, for example. A large safety study involving over 20,000 vaccinated pregnant women, undertaken by the UK's Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), has found no risks in pregnancy from Repevax, which was the vaccine used for this programme until summer 2014. Repevax is very similar to Boostrix-IPV but made by a different manufacturer. A large Australian study of nearly 82,000 babies looked at rates of autism in babies born to people who had been vaccinated against whooping cough in pregnancy. (The vaccine used in Australia is slightly different from the one used in the UK; it protects against diphtheria and tetanus as well as whooping cough, but not polio.) The study found that these babies were no more likely to have autism than those born to those who had not been vaccinated against whooping cough in pregnancy.

|

|

In this video, ten-year-old Lauren Burnell and her mother talk about their experience of whooping cough. Subtitles are available (first button in the bottom right hand corner). What whooping cough is really like

https://www.youtube.com/embed/-WAwJGJ1R4k?wmode=opaque&controls=&rel=0

|

|

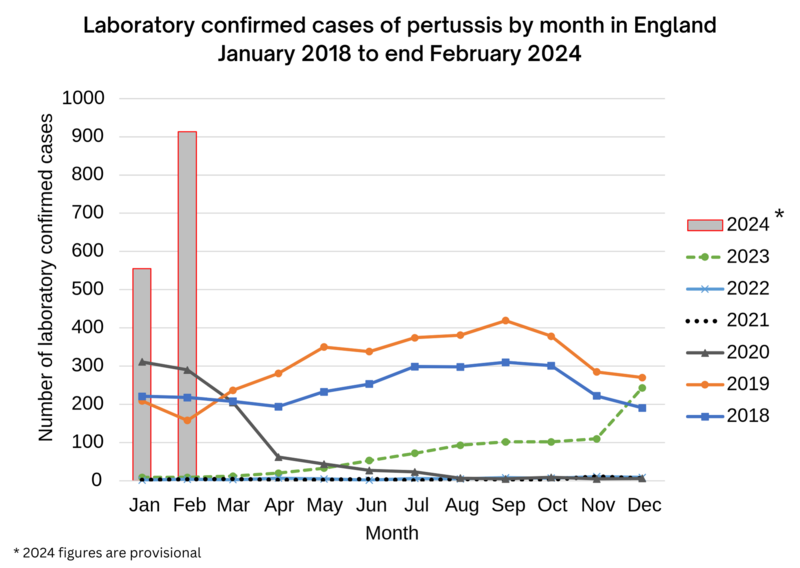

Pregnant people in the UK have been recommended the pertussis vaccine since 2012, when there was an outbreak of whooping cough in the country. During that year, there were over 9,300 cases in England alone. This was more than ten times the number of cases seen over the previous 10 years. The causes of the epidemic are not clear. The years since 2012 saw a fall in cases, although numbers are still higher when compared to the years before the 2012 epidemic. The lockdowns and social distancing measures put in place during the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a large drop in cases. But since the final months of 2023 the UK has again been experiencing an increase. During January 2024 the UK Health Security Agency said there were 555 cases of pertussis provisionally confirmed in England, compared with 858 for the whole of 2023. The number of cases appears to have increased further during February 2024, with 913 provisionally confirmed. Out of January’s cases, 22 were babies under three months old and therefore at particular risk of serious complications.

Source: UK Health Security Agency The current outbreak comes against the backdrop of a steady decline in the number of pregnant women getting vaccinated against pertussis. In 2023 vaccine coverage stood at around 60% for England, with large regional variations. London dropped from 56.7% in June 2019 to 37.2% in June 2023. This puts the gains made by the maternal pertussis vaccination programme at risk. A similar programme of pertussis vaccination in pregnancy is also offered in the US, Australia, and some other European countries. Please go to our Vaccination and pregnancy pages if you want to find out more about the safety of vaccines during pregnancy. |